Over the past two months, we published seven interviews with experienced backbone leaders. Although we approached these interviews with a loose agenda (“How have their initiatives evolved and been sustained?” “What can experienced backbone leaders teach newer initiatives”, etc.), the interviewees provided a treasure trove of nuanced advice, stories of success, and (yes) stories of failure. Instead of sticking to talking points, each interviewee gave us the real story. Lastly, our interviewees were incredibly generous with their time (and backbone leaders are busy folks!). For all of these reasons, we are very indebted to the interviewees.

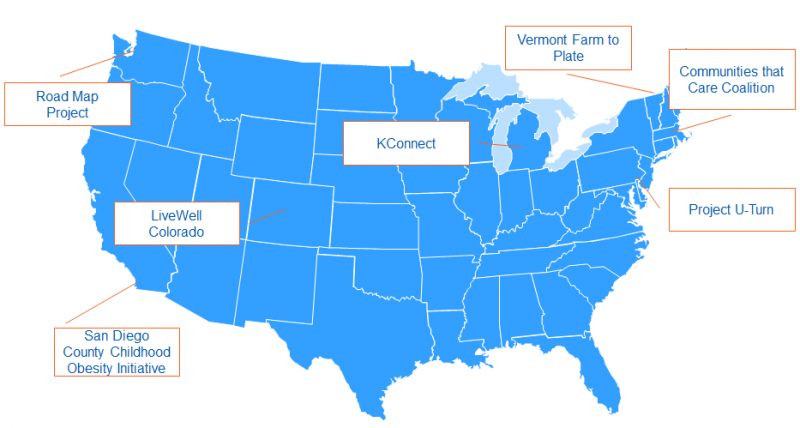

Interviewees included:

- Kat Allen of Communities that Care Coalition (Franklin County and the North Quabbin region, MA)

- Paul Doyle, Lynne Ferrell, and Pamela Parriott of KConnect (Kent County, MI)

- Chekemma Fulmore-Townsend of Project U-Turn (Philadelphia, PA)

- Gabriel Guillaume of LiveWell Colorado

- Ellen Kahler of Vermont Farm to Plate

- Cheryl Moder of San Diego County Childhood Obesity Initiative (San Diego, CA)

- Lynda Petersen of The Road Map Project (South King County and South Seattle, WA)

The interviewees’ collective impact initiatives vary by:

- Geographical footprint: 2 statewide initiatives (LiveWell Colorado, Vermont Farm to Plate), 5 regional initiatives (Communities that Care, KConnect, Project U-Turn, San Diego County Childhood Obesity, Road Map Project)

- Urban vs. rural: 4 initiatives encompass rural areas (Communities that Care, KConnect, LiveWell Colorado, Vermont Farm to Plate)

- Experience: The newest of the initiatives (KConnect) has been around since 2012, while the most experienced (Communities that Care) has been going strong since 2002

- Issue area: Education (3), health and well-being (3), food systems (1)

Top Themes and Takeaways

This blog concludes the interview series by summarizing themes from the interviews. In the comments section, we would love to hear from you – what are the most important things you learned from this blog series? What do you disagree with? What would you like to hear more about?

If you would like to share your own lessons with collective impact, we invite you to post on the CI Forum’s community forum page or add your own collective impact initiative to the growing Initiative Directory.

Keys to sustaining a CI initiative

- Evolve scope to address the right problem and to be financially sustainable. Each initiative has evolved over time. For example, as Project U-Turn’s scope broadened, they included more and more diverse stakeholders to address different parts of the dropout crisis. Chekemma Fulmore-Townsend notes that “As we understand the system young people must navigate after they complete high school, we’re increasingly involving those parts of the system.” In order to obtain funds needed to sustain itself, Communities that Care Coalition expanded its focus to include nutrition and physical activity (in addition to its original focus on substance use prevention). Kat Allen notes this broadening is in-line with CTC’s focus on youth health and wellbeing. Lastly, while LiveWell Colorado initially tackled low-hanging fruit, they have transitioned to addressing root causes of obesity. As Gabriel Guillaume states, “We came to understand that we’ll only make incremental change [by going after low-hanging fruit] and as a result we decided to focus on harder, more systemic issues.”

- Diversify funding sources, seek long-term funding. We heard from multiple interviewees about the vulnerability caused by a single, large funding source, and the importance of diversifying. “The chief sustainability challenge is having consistent, long term funding commitments,” notes Chekemma Fulmore-Townsend of Project U-Turn. “This is not a 2 or 3-year problem, and the investment needs to match the type of change you are seeking.” Many interviewees expressed frustration that funders often don’t understand the need to fund collaboration (e.g., the backbone and the supports it provides), and this remains an ongoing challenge.

- Build capacity of others. Good backbone leaders build the capacity of others to continue the work in light of uncertainties such as elected officials’ coming and going, funding fluctuations, and personnel turnover in partner organizations. According to Kat Allen at Communities that Care Coalition, “the reality is that funding can go away at any time and we have to be prepared to leave a legacy of effective strategies and population-level change. When we set up a new strategy, we are thinking about long term sustainability from the get-go… we have built buy-in and capacity so that our stakeholders are doing the work themselves.” Chekemma Fulmore-Townsend at Project U-Turn concurs, noting “To sustain the initiative, it can’t be just my job. In Philadelphia, there is a real sense of communal ownership around moving the needle.”

- Know how to speak the language of different types of funders. Gabriel Guillaume at LiveWell Colorado captured this sentiment well by saying “knowing how to speak to different types of funders is really important. Some funders want to hear the ‘collective’ side of collective impact, such as how partnerships are forming. But, others want to hear the ‘impact’ side, such as what are you accomplishing and your return on investment.”

- Share credit. Cheryl Moder of San Diego County Childhood Obesity Initiative cites the challenge of “recognizing the work of the partners, and getting partners comfortable talking about their work in context of the larger collective efforts. The more successful you are, more people want to be a part of the effort, and more you need to bend over backwards to give credit to your partners. It’s very easy to make mistakes regarding partner recognition.”

- Build trust. Trusting relationships can be built by carving out time (e.g., having a non-working lunch at each meeting), taking action together, and setting reasonable and understood expectations.

- Engage the community in authentic ways to foster community ownership. According to Paul Doyle of KConnect, “You have to be proactive and mindful of the rules of engagement [with the community]. We have more work to do around engagement, but we try to give individuals in the community the opportunity to be part of the initiative; this creates an atmosphere of ownership.” CI initiatives are putting their money where their mouth is by recognizing the sacrifices community members make through their participation.

- Focus on the benefits of partnerships. Partners will be more inclined to support the initiative if they understand what they are receiving from their involvement.

- Produce convenings that people want to attend. We are all busy individuals, and meetings increasingly crowd our calendars. Experienced backbone leaders know this, and invest in high-quality convenings.

Character traits and skills we observed about our interviewees (all experienced backbone leaders)

- Experienced backbone leaders celebrate successes while embodying urgency to do more. Remarkably, each interviewee followed statements of accomplishment (“we’re proud of our equity work to date”) with statements of sincere urgency (“but we have so much more to do”). Chekemma Fulmore-Townsend from Project U-Turn exemplified this when she said “I’m excited to see progress, but it’s energizing to see how much more work we have to do.” Notice how she is excited and not daunted by the remaining work!

- Experienced backbone leaders have an exceptional instinct for managing interpersonal dynamics. For example, Chekemma Fulmore-Townsend makes sure to include key stakeholders before reports are released: “We vet the data with leaders in the system [before releasing important reports]. Of all the things we do to advance partnerships and align to the common goal, vetting reports with system leaders prior to publication is the most powerful approach we have.”

- Experienced backbone leaders are open about their personal and organizational shortcomings. All CI initiatives are works in progress, and even in effective initiatives CI leaders acknowledge that missteps happen. As Gabriel Guillaume of LiveWell Colorado noted, “Something always true about collective impact work is that mistakes are inevitable. Learning from them is your most important responsibility.”

Note: Backbone leaders often embody “system leadership.” To dig deeper into traits of a system leader, I recommend reading The Dawn of System Leadership by Peter Senge, Hal Hamilton, and John Kania.

Ideas worth considering

- Given the size of their key roles, compensate working group chairs for their time. Vermont Farm to Plate invests in working group chairs as a key part of the network. Their four working groups with co-chairs receive $5,000 each, the working group with one chair receives $7,500, and chairs of cross-cutting teams may receive stipends if needed. Vermont Farm to Plate also provides chairs with leadership development opportunities, such as project management and facilitation training. Ellen Kahler claims that “this not only helps the working groups, but also the chairs’ own organizations. Investing in working group chairs allows us to have a lean backbone of 4.5 full-time equivalent staff.” (note that Vermont Farm to Plate is a state-wide initiative)

- Compensate community members for their participation, but in a thoughtful way. According to Lynda Petersen at the Road Map Project, “some people get paid to go to meetings all day, but parents don’t, and we need that perspective at the table.” A legitimate point of view (held by some community organizers and others) is that there may be risks in compensating community members, as it could reinforce power dynamics or incentivize community members to say what others want to hear. Thus, this approach should be done thoughtfully.

- Create an Equity & Inclusion Workgroup to help the whole initiative embed equity in its work. It is essential to design and implement CI initiatives with a priority placed on equity (see Collective Impact Principles of Practice). Paul Doyle at KConnect comments that their Equity & Inclusion Workgroup “will help the other workgroups utilize an ‘inclusion filter’ approach to insure we consider the factors that impact all children in their strategy development process. By doing this, we can create an opportunity for individuals who are not close with equity work to increase their competency and understanding.” In a similar vein, the Road Map Project uses a racial equity template when planning strategies.

- Support programs and system-level reforms. “What we’ve found is that people don’t organize around the word ‘policy,’ at least initially,” says Gabriel Guillaume at LiveWell Colorado. “That’s why programs and more tangible terms and outcomes are so critical. I’m not going to knock on doors for ‘policy change.’ But, if a group of parents want to start a ‘walking school bus,’ which is highly programmatic, then people will get involved in that. Programs are important in their own right, but they also reveal systemic barriers that programs themselves will rarely overcome.” Note: this topic is also addressed in Collective Impact Principles of Practice.

- Reinforce a collaborative culture through communication protocols and high-quality deliverables. Ellen Kahler at Vermont Farm to Plate gave us this excellent example: “It took time for people to understand that they can show what their organization is doing while being part of a larger effort to strengthen Vermont’s food system. To reinforce this message, my Communications Director has built a community of practice with communications specialists in network members’ organizations. They coordinate with each other so that when individual organizations create a press release, they include two sentences that situates their organization within the larger Farm to Plate context.” Additionally, Vermont Farm to Plate is very intentional about their deliverables (e.g., strategic plan, website) having a consistent look and feel and using consistent messaging and a common language. For network members, this creates awareness that they’re exiting their own organization’s space, and entering a collaborative space.

Additional thought-provoking comments from our interviewees

- To reinforce a collaborative culture, don’t have every organization on the Steering Committee. According to Vermont Farm to Plate’s Ellen Kahler, “Perhaps a bit counter-intuitively, with our steering committee it’s not about having every key organization at the table. Rather, we wanted our steering committee to reflect the structure of the Network. If you have the expectation that every interest group needs to have a seat at the table, then everyone will speak from their own organization’s perspective rather than from the larger system perspective.”

- We live in a unique moment where the time is ripe to push for equity. If we don’t push, the moment may be lost. As powerfully stated by Angela Glover Blackwell in a recent CI Forum convening (see video here), the U.S. faces a turning point regarding equity. A number of our interviewees are stepping into this moment by having difficult equity conversations. “Equity has always been part of the Project U-Turn conversation, but the national conversation around equity gives Project U-Turn and its partners permission to discuss it more directly than before,” says Chekemma Fulmore-Townsend. Lynda Petersen concurs, stating “across our country there’s a real focus on racial equity, and this year we’ve had so many conversations about what that looks like in the Road Map Project. We’re far from figuring it out, but I’ve appreciated the courageous conversations that we and many in our communities are having.” At the same time, Lynne Ferrell of KConnect posits that addressing equity requires getting comfortable with ambiguity: “We may not fully know how all of this [will] unfold, but we [do know] that the status quo [is] unacceptable.”

- To build relationships, you have to sincerely care about people. “I think fundamentally you have to care about people,” says Cheryl Moder at San Diego County Childhood Obesity Initiative. “You have to care about why they’re there. You have to care about their motivations, who they are as people, partners, and individuals. You don’t have to like everyone, but you do have to care about them to a certain degree. And it can’t be superficial. You’ll have difficult times, but at end of the day, they’re people! Ask about their families! Know enough about them to know that they’re real people.”

- Backbones are not “neutral facilitators,” but “transparent facilitators.” According to Chekemma Fulmore-Townsend at Project U-Turn, “we have gone from a neutral facilitator to a transparent facilitator. We have a perspective, and we can still facilitate without hiding that. That was a huge shift for us.” See this blog by my colleague Chris Carlson on why “neutral” may not be the right word to describe backbones.

- Acting together can create just as much (or more) alignment than planning together. “A lot of collective impact leaders I speak with struggle with how to get collective efforts to stop the process of spin – they focus on the ‘collective’ for too long and never get to the ‘impact,’” according to Gabriel Guillaume from LiveWell Colorado. “This happens a lot because the planning process can take a very long time. But I think a lot of people forget that action creates alignment more than process does.” Similarly, Lynda Petersen at the Road Map Project contends that “If all we’re doing is ‘problem gazing’ at the data, what impact are we having?”

In the comments section below, we’d love to hear from you: what can you apply to your CI initiative? Where do you disagree? What do you want to learn more about?