This past April, over 700 attendees and hundreds more online viewers joined us for the livestream event Beyond Seats at the Table: Equity, Inclusion, and Collective Impact, a keynote at the 2018 Collective Impact Convening in Austin.

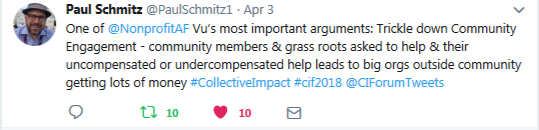

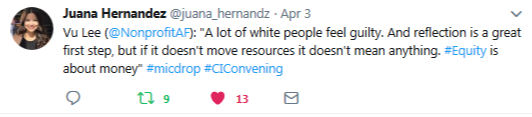

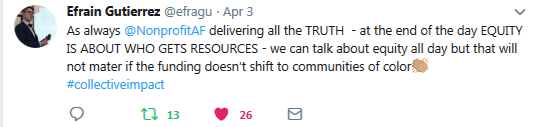

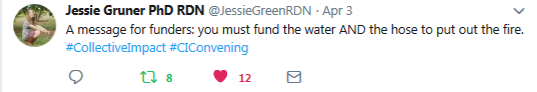

The Collective Impact Forum is excited to share with you the video from this livestream event, as well as a transcript of the keynote remarks by Vu Le (Rainier Valley Corps), with introductory remarks by Sheri Brady (Aspen Forum for Community Solutions.) We have also included tweets below from attendees and livestream viewers who shared their thoughts during the session.

Find below both videos of the keynote and the following panel discussion.

Beyond Seats at the Table: Equity, Inclusion, and Collective Impact

Video and Transcript

[Introduction by Sheri Brady]

I am very excited to introduce our keynote speaker, Vu Le, the author of the NonprofitAF.com blog. I had to remind myself that I couldn’t tell you what AF stood for because trying to be professional. It took me a moment, sorry about that, which I read religiously every Monday because who doesn’t want to be a nonprofit unicorn? In addition, he is the executive director of Rainier Valley Corps which has the mission of tackling systemic injustice by developing leaders of color, strengthening organizations led by people of color, and fostering collaborations between people of color. Vu is here to challenge us to think about equity, inclusion, and collective impact. Please join me in welcoming Vu to the stage.

[Remarks by Vu Le]

Hi everyone. Thank you so much for having me here. I love Austin, the Portland of Texas. Did you know there is a cat café here? It’s the Blue Cat Café. You can go there and you can get a coffee, and you can adopt a cat. That’s really cool so check it out.

I’m also really excited to be here. I’m actually kind of surprised to be invited after all the things I wrote about collective impact, and I know that you’ve had some amazing speakers. Angela Glover Blackwell especially with PolicyLink, I watched her entire keynote speech and I think she really raised the bar on this conversation. I am here today to lower it a bit.

This is also the first time where I am speaking at a town and some of my team members are here. So Ananda, our managing director, and Uma, our capacity building coach, are actually here, and that defeats the entire purpose of me leaving to give a keynote speech somewhere else. Because they are here I am leaving after this to go back to Seattle. They are going to remain for the rest of the conference. So thank you again for having me.

Beyond seats at a table, equity, inclusion, and collective impact—by the way, there’s going to be pictures of baby animals on every slide. This is on purpose because Japanese researchers did some study when they discovered that looking at pictures of baby animals actually increases your productivity. So there’s going to be pictures of baby animals on every single slide except like three of them, and they have no relation to anything I’m talking about whatsoever. Just keep that in mind but I spent a lot of time trying to select the pictures of the baby animals, like very strategic, OK?

So what are we going to talk about? See, it’s working already. You’re more productive. What are we going to talk about? We’ve been talking about there’s equity and diversity and inclusion, EDI. It’s like the new coconut water. Everyone’s been talking about it all the time, right? You just drink it after hot yoga or whatever. That’s what we do in Seattle, and everyone’s talking about collective impact, etc., but there’s been a lot of challenges. I know there are a lot of leaders around the sector who have been bringing up these challenges. I want to examine them a bit, and really come from this perspective of someone on the ground who has been involved with some collective impact efforts, who has been leading organizations led by communities of color, and really kind of bring it down to the ground a bit because I think that’s one of the challenges of collective impact. It’s so broad and whatever, 30,000-feet level, etc. How does it affect people on the ground? So I’m going to bring that perspective.

A few disclaimers first. Disclaimer number one, I have a five-year-old and a two-year-old, and I have not slept in five years. Having a baby is like getting a multiyear federal grant. At first you’re like, “Yay,” and then it’s like, “Oh, this is so much work.” And you can’t really give it back. It’s rough. So I made extensive notes on this presentation, then I had forgotten all of it. Disclaimer number two is that I don’t claim to be an expert in anything. I have a blog. It used to be called nonprofitwithballs. Now it’s NonprofitAF to be less provocative. The AF stands for “And Fearless,” “Nonprofit And Fearless.” And I run a nonprofit. That doesn’t mean that I actually know everything. This is just one person’s perspective so please feel free to push back. We will have some time to do a little bit of a table conversation and then some Q and A and I would really encourage you to challenge. I think our sector is full of really brilliant, extremely good-looking people, and we don’t—sometimes we beat around the bush a bit and we don’t really challenge one another directly so please feel free to completely disagree with anything and everything that I say today. Disclaimer number three is that I don’t claim to represent anyone except myself. I think it’s easy to say, “Oh, Vu. He’s up there on stage. He must represent all people of color, all executive directors in Seattle or all attractive intelligent people everywhere.” No, it’s just one dude. If you write a blog long enough someone is going to invite you to Austin to give a keynote speech.

OK, what’s going well with collective impact? I remember collective impact a few years ago, I think it was about seven years ago. I was at the Youth Executive Directors of King County, and that was a collection of organization EDs who got together to discuss, “Hey, it seems like early learning is doing really well coalescing around some common goals and metrics, and we youth development people, we don’t. So we really need to do this.” So we got together and someone passed around the SSIR article, and I read that, and it’s like, “This is awesome. This is great. We should be doing more things like this.”

I remember that moment and thinking this is really cool, and I think in many ways collective impact has done some amazing stuff. I mean I skimmed through the 124-page report and the 24-page executive summary. There’s a lot of good things that happened and it’s been incredible. I think it has actually forced many of us nonprofits to think more collaboratively, not just amongst ourselves but also with other sectors. In many ways it started to really make me think about this nonprofit hunger games that we all have where we’re competing with resources. Nonprofit hunger games, yeah, right?

And so it’s been great. It’s been addressing a whole bunch of challenges from homelessness to early learning education. I’ve seen it working in Seattle. There’s lots of great things happening in Seattle, and I really want you to feel the sense of appreciation and accomplishment in all that you do because I know this work is really hard, but in many ways it is working so please feel that sense because I’m going to spend the next 30 minutes criticizing collective impact, OK?

Frustration with collective impact. I don’t actually know what this is. I think it’s a baby fox. There are some great things about collective impact, but a lot of communities of color, leaders of color have been very, very frustrated with how collective impact has been done.

I remember talking to a funder once. It was an environmental funder, and I was talking about how challenging it has been to get communities of color to get the resources that we need to do environmental work. And the funder, I remember him saying, “Do people of color care about the environment?” He was actually—this is a really nice guy. I was trying this thing where I’m trying to be inquisitive instead of just stabbing people, and I said, “Why do you ask that? Why do you think people of color—why?” And he went, “Well, it’s because we’ve been trying to do this collective work, trying to bring all the organizations together, and we’re missing the voices of these communities of color so therefore I’m wondering if they care about environmental work.”

This is the challenge that we’ve been having, right? That this work is just at this level where people in power are often not the people who are most affected by injustice, having all the influence and resources to do this work. It’s been very frustrating.

I remember just a few years ago when I got a call from an executive director of color who said, “Can we have a meeting? Let’s have a meeting. I’m calling all these EDs of color together. We’re going to go to a bar, we’re going to meet.” We do a lot of meetings at bars, and it was in response to the fact that yet one more collective impact backbone organization was getting a multimillion dollar investment and going around asking these small organizations led by communities of color to join workgroups, and to fill out surveys, and to attend a summit, all without any sort of funding whatsoever. We had this conversation, we were just so—we were just like drinking our dirty martinis and just talking about how just horrible it is. One lady said that she had spent about 20 hours a month for the past three years for free, and not fundraise for her own organization. This was not an isolated incident. This was like happening repeatedly, over and over again in Seattle. So there’s a lot of frustration going on. I’m going to point out some of these.

It’s very top-down, one size fits all, linear, and I know this is from my own perspective and maybe it’s done better in your communities but I think in Seattle and in King County there’s been so many challenges. We have countless efforts where it’s kind of like “this is the way that it’s going to be done, here’s our logic model, and here’s our agenda that we’re going to drive.” And many times communities of color or communities with disabilities or LGBTQ communities or rural communities don’t really follow this sort of linear sort of path of doing things, and yet this is what we are expected, and we get punished for not following these very prescribed steps.

There’s also been a lot of backbones acting as gatekeepers, and I don’t think that they mean to do this intentionally but in Seattle it’s, this is what’s—I remember having a phone call, a program officer called me because we had applied to a grant, and it was about collective impact. It was basically about funding small organization. It was $15,000 to a small organization to be involved in these collective impact efforts, and my organization, the Vietnamese Friendship Association back then, had applied. I got this phone call from a program officer. She said, “Are you in a secure location?” I was like, “Yeah, I’m in the bathroom.” She was like, “I need you to revise your proposal to be more aligned with the collective impact effort or else you’re not going to pass through to the site visit phase. We never had this conversation.”

This is what’s been happening. If you don’t align with a collective impact organization, you are at risk. You jeopardize. Your funding may be jeopardized. This has happened many, many times. This has been leading to a lot of the drinking among communities of color-led organizations. The forced alignments.

I remember I revised our proposal and resubmitted it, and then we had a site visit. Eight people, all white, came to our site visit for a $15,000 dollar grant, and the question they kept asking was, “How do you align with this collective impact effort? How do you align with it? Where are your priorities? Where do they align?” I was getting really fed up, and this was $15,000 and it was just not worth my integrity at that moment, and I basically got very angry and I said, “We will align where we align, and when we do not align, we will always prioritize the needs and the priorities of our communities, and if this is not a good match for this grant, then I will understand.” They were taken aback, like, “Please don’t write about this on your blog.” We actually got that grant. It was $15,000 but this is what we were dealing with. This was the mindset that collective impact just went, and it just started spreading, and it’s been leading to this thing that my colleague, Jondou Chen, calls “weaponized data.”

I know data is a huge part of collective impact. Well, this is another challenge for our communities. Data has been both a weapon to beat our communities with and a shield to prevent any sort of feedback from happening. And this manifests in the data resource paradox where you need really good resources to get good data, but you can’t get good data without good resources. So small grassroots organizations are continually screwed over and over again.

I think there’s another frustration among many organizations led by communities of color, and that is this sort of “gap-gazing” someone calls it. An academic researcher calls it gap gazing, but we just look at these—we spend so much time doing research that points out stuff that we already know basically, OK? Do we really need another study that says that black-led organizations have ten times fewer resources and assets than white-led organizations? Oh, that is so shocking. Do we really need to spend 18 months finding research that kids of color are not doing as well? I know there’s disaggregated data. I think that’s really important, but I think we’ve gotten into this point in some ways where the danger is that we spend all this time just researching.

I was talking to a collective impact organization who said, “Vu, can we partner with you?” I was with the Southeast Seattle Education Coalition which was also a collective impact effort lead by communities of color, and this person said, “Can we do this summit? We have some amazing data about the education achievement and opportunity gap, and we want to present it to the community.” And I checked in with the community and everyone was like, “What? What are you going to do? You’re going to have this summit. You’re going to feel really good about yourself. You’re going to ask me to bring all these leaders of color and community members of color to your summit. You’re going to present this data that says that our communities are not doing as well, that kids of color are not doing as well as white kids. What does that do? You took all this funding to do this research.” We didn’t do that summit.

But that has been the case over and over again. I think there’s this danger of just like this sort of navel gazing of like this gap out there, but maybe the funding that funded this research that’s completely unsurprising should have just gone to organizations led by communities of color so they could do something about that.

There’s also this illusion of inclusion. My friend Sharonne Navas coined that term, illusion of inclusion which is basically tokenizing communities, right? It’s asking people—I mean I get asked all the time now to join a summit or an advisory committee. Leaders of color get asked all the time because we want that illusion that it’s very inclusive, and I think this is actually more dangerous than not having the inclusion itself in many ways because it makes us very complacent. It makes us think that we’re doing something well when it’s the opposite.

And I think this could lead to something that is extremely dangerous which is trickle-down community engagement. Community engagement has been a big thing as you know, and in Seattle it is huge. I always joke that if you’re in Seattle and you’re walking down a dark alley at night and you feel like someone’s following you, it’s probably someone trying to do some community engagement. It’s like, “Psst, hey buddy. You want to attend this equity summit? We got some sticky dots for you. You get five dots, you can put them on separate priorities or do you really care about one or two where you can put more than one dot on those priorities?”

I was talking to another executive director who said, “Vu, have you noticed that everyone is getting paid to do community engagement with communities of color except communities of color?” This is very dangerous. Funding goes to white-led mainstream organizations who oftentimes do not have the connections and the relationships and the trust with communities on the ground. So then they trickle down small amounts of money to these smaller organizations but they claim 95% of the resources. These organizations do a bunch of work on the ground, and then they become kind of thankful oftentimes. They’re like, “Oh, my gosh. I got $5,000,” and then they do all this work and then the credit trickles back up and starts this horrible, vicious cycle over and over again.

I remember when I was leading the Vietnamese Friendship Association that this happened. An organization, a very large, well-known national organization got a huge amount of money from the Families and Education Levy, and they were not able to reach to kids of color. So then they went to my organization and they said, “Hey, we want to partner with you. We want to do some community engagement and maybe some partnership. Can you help to organize this academic workshop for kids of color?” So once a month we would—I think it was once every other week or so, we would bring in a hundred kids of color at the school, partner with the school. It was for three hours learning math and English and everything with kids, low income, kids of color. We did this for a year. We got a total of $2,500, and every single invoice was itemized. They asked for every single receipt or every pencil we bought and everything.

And I remember that because this is one of the biggest lessons I’ve learned in my career, when to say no, when to realize you’re being screwed and your communities are being screwed. And of course the organization thought this is great, you know, and they were able to claim that they were able to engage with the community, and so they got more money, and our organization was just like, “Oh, yay, we got $2,500,” until we realized, “Oh, crap. That was not a good decision at all.”

But this is something that happens over and over to marginalize communities-led organizations, again and again. This is extremely destructive and unfortunately I’ve been seeing a lot more of this in collective impact efforts.

In many ways collective impact, when it’s gone wrong, it is like the Borg. Who watches Star Trek? All right, nerds. In Star Trek, there is a villain called the Borg and they are like this hive mind that goes out and annexes everyone and resistance is futile. Either you’re in the Borg and you’re part of this hive mind or you get destroyed. Once you’re in the Borg it neutralizes any sort of individuality, and I think in some ways when collective impact is done wrong, that’s what happens. We become annexed by the Borg. It’s like we have to determine whether we want to join the Borg or be destroyed by the Borg. And that is not a good choice.

Now I know there’s challenges, and I know there’s been lots of conversations around collective impact 3.0, and incorporating more equity into this work. I appreciate that. I know that the Collective Impact Forum has been extremely transparent and really interested in having these conversations. I mean publishing some of the blog posts I wrote, that’s pretty brave.

But a challenge is that we are trying to recover from collective impact. It was not designed by the people most affected by injustice. If it had been designed by them, then it would look completely differently. The elements would be different.

So I asked my colleagues of color, “What would it look like if collective impact had been designed by communities of color?” It would be grounded in equity, race, intersectionality, OK? We can’t get away from talking about race. We can’t. We just can’t. So much of the issues that we deal with are systemic issues stemming from racism, and if we’re not willing to talk about that, I don’t think we can address this.

In Seattle, we’ve had redlining where people in the central district for a long time. In the lease, if you buy a house, there was language in the deeds that say if you buy this house, you cannot sell this house to a person of Negroid or Mongoloid descent. And this was just like, I don’t know, 50 years ago, and because of that has all these repercussions that we’re dealing with right now as people of color are being pushed out of their neighborhoods that they historically were forced into. So because of racism they were forced into the central district. Because of racism, they had to live in southeast Seattle and now with Amazon and Boeing and others coming in, Google, etc., and driving up prices, the people who were living in these areas can no longer live there. They’ve been there for 20 or 30 years and now they’re getting pushed out even further. How do we do this sort of collective impact work and we’re not willing to admit that a lot of the challenges that we are dealing with stem from systemic racism and injustice? We cannot.

Communities serving a common agenda. This is another issue. You can’t just say common agenda because people will take that to mean anyone can come up with a common agenda, anyone with the power and the influence and the resources. Someone told me once that they were doing—she was very frustrated, a colleague of mine doing collective impact around homelessness, and all these organizations’ board members were getting together in this room talking about homelessness. And they noticed there was someone just really loud outside the door, a really loud person begging for money right outside where they were having this meeting. It was someone who was experiencing homelessness, and my friend was just really frustrated because the people in the room stopped and said, “Can we do something about this? Can we get this person to move somewhere else?” That is disturbing. They were talking about homelessness. Here was someone who was actually experiencing homelessness. Why wasn’t he in the room?

This is something we have to think about all the time. Who is driving these agenda? Are the people most affected by injustice driving the agenda? Or simply the people with the most resources and power?

Shared measurement that prioritizes lived experience. That’s another issue that we get discounted all the time. “Oh, here’s our shared measurement.” “Well, that’s not my shared measurement. That’s not my community’s. That’s not what we—.” “Well, the data say this. This is what where we’re going. This is what the majority of the group, the ones who were able to attend that summit determined is the shared measurement.”

Mutually reinforced activities that build on trust and strong relationships. This is something that we have to value. I think in many ways collective impact has moved way too fast, and it leaves people behind all the time. Many communities take time to build relationships and trust. We’ve gone through wartime trauma, systemic racism, all sorts of challenges, diaspora, gender dynamics, all these different things and yet so many of these activities are just like mutually reinforcing but for whom?

Culturally responsive communication. I talked to a collective impact effort once who said, “Vu, we want to have this summit. We want to do this collective impact summit around education.” And I said, “Please don’t do that. Please don’t do a summit, OK? Just don’t. You’re asking for my opinion and I’m going to give it to you. Just don’t have a summit. Parents of color and others, we’re just sick of summits. We’re sick of going to these gatherings where you have these simultaneous translation things like the UN, and then you have sticky dots and all this stuff, and you’re just going to bring a bunch of people together, they’re very confused, then they get very hopeful that something is going to change, and there is absolutely no follow up at all. Just don’t do it. Just spend your time out there building relationships. Talk to people one on one. Go where people are. Don’t make them come to you and your summit because that’s not how we communicate. That’s not how we communicate.”

They had the summit anyways, and the same thing happened that I had predicted. People became very jaded, and the kicker was they had called me a month before the summit and said, “Vu, would you mind translating this flyer into Vietnamese for us and do outreach for us. And also, this is like really urgent. Can you get the translation done in two days?” Literally, this is what I got. Where did the funding come for this? It was deeply insulting to think that I would just suddenly drop everything to translate this, right? But this has been the norm. People don’t even think about it. They don’t think about how deeply insulting it is, and inequitable it is to our communities when that happens.

Community-led backbone organization. This is another challenge for collective impact. So many backbone organizations are not led by the communities most affected by injustice. That is an issue. Equal access on direct service and systems change, that’s another complaint that POC leaders in Seattle had which is that suddenly in Seattle you could apply to grants in the past directly for your own organization’s work around education, after school program, mentorship. Now we’re being told, “You know what? You need to work with this collective impact organization, and, in fact, we no longer fund direct service. We don’t fund direct service anymore because we’re now funding collective impact.” That happened over and over. My own organization, we lost $50,000 one year because of that. Just like, “Sorry, we don’t fund this anymore. We’re putting all of our money into collective impact because that’s what the data shows, that’s what we should be doing.”

Equitable distribution of resources. So many organizations getting all the funding. We’ll talk about this in a moment. That was a lot of text so the next image is just a baby wombat.

I want to talk a little bit about my own organization, Rainier Valley Corps, because in many ways Rainier Valley Corps was formed to address many of the challenges of collective impact, and there are several things that we don’t even consider when it comes to collective impact which is like operating support and leadership and capacity building. All of these things need to be there for collective impact to work. Many of the organizations cannot be involved with collective impact because they are just scrambling to stay alive.

After the election one of the leaders of color in our community, he told me, “I spent five hours on YouTube learning how to do QuickBooks.” This was right after the election. This was a well-known influential black leader in our community. We should be out there organizing people, and he was doing all this work with QuickBooks. This is what we’re doing with our leaders out there. If we don’t think about all these different challenges, then collective impact is not going to be as strong as it could be.

So Rainier Valley Corps, my organization was founded three years ago. Our first program was to bring more leaders of color into the work which is another critical missing piece. If we don’t have leaders of color, how are we going to do collective impact work effectively? And that branch that we started, we sent in leaders of color to organizations led by communities of color. They work there for two years. We pay their salaries and medical insurance, and they have been doing incredible work. We recently expanded our work into our mission. It’s providing operation support where we will, instead of teaching people how to do operations stuff, we just do it for them. We will just handle the QuickBooks for them because our leaders should be out there doing collective impact work or systems change work. We don’t think about this. This is just phase one of this work, building leaders, building organizations of color. As we develop this, we will go into doing more systems change work now that our leaders are strong. I think this is something that we really have to get a handle on.

My five-year-old just joined little league. I don’t know why I’m bringing this up. I have a point. Little league is, in some ways, like collective impact, right? All these kids playing on the same team with shared measurements, etc. I don’t know anything about sports but I think it’s good for him to be doing this. But we have a lot of kids who are very poor and they—my wife is a fourth-grade teacher and she knows there’s lots of kids who come to school but they haven’t had breakfast. They might be really hungry. Imagine when you have a little league where several of those kids have not had breakfast for three days. How is the team going to be doing this work effectively? How is it going to win? This is what we have to think about when it comes to collective impact.

Who are these organizations and leaders who most need the resources to be effective contributors to collective impact work?

Equity and money. This is one of the most frustrating things for leaders of color, the ones that I’ve talked to. We’ve been talking about equity. We write articles about equity, and now failure is like the new kombucha so we talk about all our failures all the time around equity and we feel really good because, “Oh look, we failed around equity and now we’re being transparent about it.” That’s great. I mean that’s great.

At the same time, equity is about resources. It’s about money. It’s not about talking about equity. It’s not about writing papers about equity. It’s not about whatever summits about equity. At the end of this, when all the rhubarb is harvested, who is getting the resources? Is it the communities most affected by injustice? Are they getting the resources? The most resources to lead in this work to address inequity. That is when it matters.

All of this guilt that we’ve been feeling. There’s a lot of white guilt going on. It’s like, “Oh yeah, we did this and as a white man I contribute to this,” and all this stuff. That’s great. That’s a good step. That’s a good first start. But if your guilt does not move resources to the communities most affected by injustice, it is useless. Equity is about money.

I know you’ll be doing a lot of workshops and thinking about things. I want you to go into these workshops thinking about this question, all of it. Does it move resources to the communities most affected by injustice?

There’s a lot of urgency in our work right now. I know there’s just been, after the election, it’s been just really awful for a lot of our community members. One of my colleagues, she does home visits. She was telling me how she was visiting this single mom and I think a six-year-old. All of the curtains were drawn. As her eyes adjusted, she saw all these numbers written out and taped to the wall. She said, “What’s going on? What’s with all these numbers?” The mom said, “These are the numbers that I want my daughter to memorize. They’re phone numbers. I want her to memorize them in case I don’t come home one day.” This is what we’re dealing with so we cannot afford to doubt ourselves. And we can’t afford not to talk about these hard difficult uncomfortable things like race and intersectionality. I don’t think this work can be done if we avoid the uncomfortable conversations. A lot of community members are counting on us.

So here’s some concrete things. It’s going to be a lot of text.

FOR FUNDERS

- Fund organizations led by communities most affected by injustice. Again, you got to do this. It can’t just be whoever writes the best grants gets the resources. That’s not equity at all. Fund the heart, the pancreas, livers, not just the backbone.

- Provide multiyear general operating dollars. My god. I’m really proud of that one.

- Get over archaic things like overhead. It’s not a thing anymore, OK? Stop it. That’s just so 2008. Overhead. We’re trying to collectively put out the fires of injustice and some of you are still going, “Hey, I want to make sure the money I’m giving you to put out the fires is going to the water and not the hose. What is your hose-to-water ratio?” We can’t do our work if that’s what you’re thinking about now, OK?

- Fund faster. Take more risk. If it takes you longer than it takes for the average couple to conceive and give birth to a baby, it’s taking too long.

- Learn from conservative orgs and funders. This is very interesting. There’s been lots of research around conservative funders and liberal progressive funders. The progressive funders are always slower, more methodical. They take forever. Whereas for many right-wing funders like, “Oh, if you’re against science and immigration, we’re just going to fund you for 20 years and trust that you’re just going to do things that will help us to increase xenophobia in the world.” It’s ironic and it’s awful.

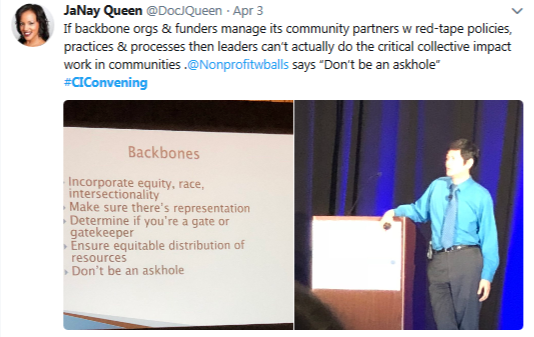

BACKBONE ORGANIZATIONS

- Incorporate equity, race, intersectionality into your work. It is not too late. Make sure there’s representation in your work. If you look around the room and it doesn’t look like the people you’re serving, that’s an issue. You might need to slow down.

- Discern if you’re a gate or gatekeeper. That’s something I learned from my team members here. Are you a gate or are you the gatekeeper? Are you lifting up communities? Are you withholding funds and relationships?

- Ensure equitable distribution of resources. Again, don’t ask people to do stuff.

- Don’t be an ask-hole. This is when you go and you ask people to do stuff for free or you ask them for stuff and then you ignore everything that they say, you’re an ask-hole. Don’t be one.

ORGANIZATIONS LED BY MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES

- Have the audacity of ambition. That 25 hundred dollar guide, that was not audacious at all. That was survival mentality. We have to get over that. Add a zero to your ask, right?

- Learn to play the game better. I know the game is inherently terrible. It’s awful. It’s the loudest voices that win. People who can write the best grant proposals. It’s the ones who have the relationships. They’re the ones who win. And we, in many ways, have to learn unfortunately while we work to change the game.

- Know when to say no. If a collective impact effort feels yucky and tokenizing, don’t be involved. And be louder. Give feedback. Refuse to be tokenized.

That was a lot of text so the next four slides is just pictures of baby animals. There’s a little hedgehog. A little mouse with a teddy bear. Who made the teddy bear? It’s so small. I don’t know. Here’s a bunch of sea otters cuddling. I know. Here’s a possum. His name is Cashflow.

I want to end though with a note of appreciation. I know I’ve been yelling at you a lot. But I do appreciate all the work that you do. I think when collective impact is amazing it is not like the Borg. It’s more like Voltron. Who watches Voltron? All right. Cool. Voltron reboot on Netflix is amazing. In Voltron, there’s this giant space robot but it’s made of like five smaller robot lions. The lions are awesome, and they each are amazing in their own right. When it’s needed, they all assemble into this giant space robot warrior that defends the universe. I think that’s when collective impact is working at its best. We know when we can combine and when each of us are strong in our own right.

I know I’ve been criticizing you all a lot. I do though want to end with just a note of appreciation which is I know this work is hard. It’s easy for me to fly in from Seattle and to criticize you all on stuff you could be doing better. The reality is this work is so complicated and all of us are needed.

I am especially appreciative because again, my family came from Vietnam. We lost everything. My dad was put into re-education camp because he fought against the Communists and they won. So then we had to move and we lost all of it. The worst thing was we lost the sense of community. Everyone that we knew was gone. All of my friends were gone. My teachers were gone. Our neighbors were gone. It was a lonely, cold existence in Philadelphia. There was all these nonprofits that got together. It was this collective of nonprofits working, helping us to get clothing and food. Helping me to enroll in a school. I think that is what our sector does at its best.

I know times have been really dark lately. I think our sector is often the beacon of light when it is darkest for our communities. All the things that you do every single day may not be appreciated and no one may come back and say, “Thank you,” to you. But I don’t want you to feel that right now because this is important work. Your work matters. It helps people like me and my family. It helps to restore a sense of community that we had lost. I really want you to feel that as you enter the next three days doing this work because you can always find ways to improve.

Please take a moment just to recognize how important your work is because it matters.

Thank you.

Share Your Thoughts

We would look to forward to hearing your thoughts about this session and what resonated for you. Please feel free to share your comments below.